Once upon a time I was a young trumpet player. I really didn't like playing the trumpet. I wanted to play the French horn but was considered too small. So I got put on the trumpet which, to be honest I didn't enjoy. I also didn't do any work. So it got to the point where an ultimatum was made - either I had to quit or had to start putting the hours in. I really didn't want to continue on the trumpet, I was still told that I was too small for the French horn, but there was a solution! Like very many French horn players before me I got put on to the Tenor (*) horn for the time being.

I loved the Tenor horn. I thought it was much more interesting than the trumpet. My favourite piece was Leslie Pearson's "Seven-Up" The Really Easy Tenor Horn Book. And was put my first music ensemble - The South West Birmingham Area Training Wind Band. When I started I really didn't know anything and I worked out I (thought) I could get away with this by copying the fingering of the tenor horn player sitting further up the section.

And then I grew a bit and got provided with a French Horn and moved on from the tenor horn. And like many French horn players I didn't really look back. The French horn has amazing repertoire and plenty to keep us busy. Then I got into playing period instruments and eventually started playing with The Prince Regent's Band.

One of the first PRB projects came about because of the Adolphe Sax bicentenary in 2014. The group had started to investigate the career of the Distin Family, a group of musicians who had brought Adolphe Sax's "saxhorns" to the UK and who had been some of the most influential and busy musicians of the 19th century. Therefore I got the chance to dig out the Tenor horn again and rediscover this instrument.

It was quite a steep learning curve. Some French horn players prefer to use an adaptor so they can use their French horn mouthpiece on the Tenor horn. I'm used to swapping mouthpieces as I swap horns normally so that, plus the fact that instruments normally work best with the mouthpiece it was designed to be played with, meant I decided to go for it and use the, much bigger, Tenor horn mouthpiece.

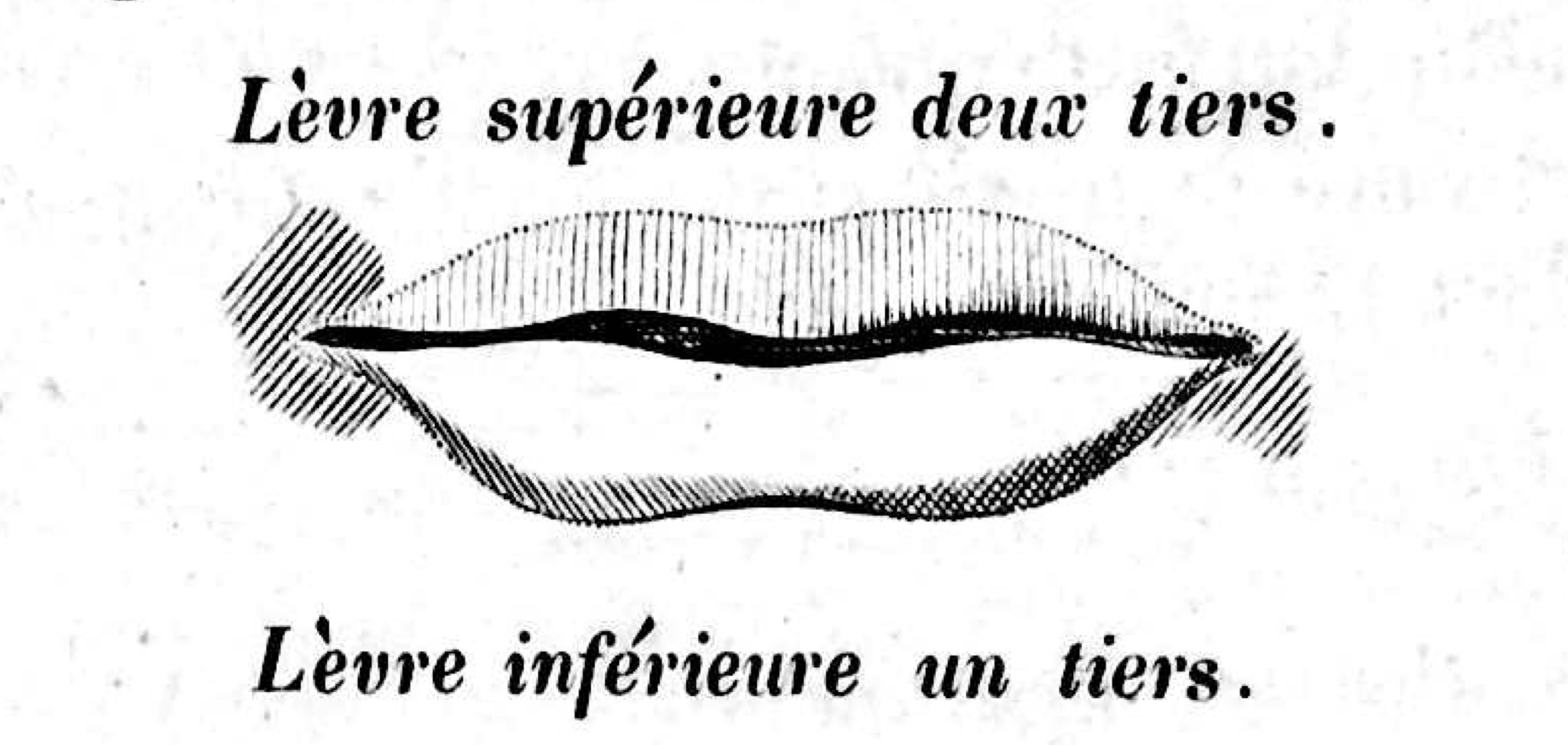

"De l'embouchure" from Méthode complète de cornet à 3 pistons ou cylindres by Niessel (Paris, Schonenberger, c.1844).

The big break through for came for me after I'd spent some time looking at French horn, cornet and saxhorn methods from the 19th century. Many of the earliest cornet players were initially horn players rather than trumpet players so there are a number of 19th century methods written by the same authors for both instrument. Plus, as the saxhorn was growing in popularity, we have a number of sources for the family of saxhorns. For me it suddenly made the tenor horn much more easy to play once I remembered that French horn players are encouraged to put the mouthpiece on their lips so it's two thirds on the top lip and one third on the bottom whilst it helps with the saxhorn if the mouthpiece is more evenly balanced between the two lips.

Thanks to a mixture of sources (many many thanks to The Bate Collection in Oxford, and Jeremy Montagu and his own collection) I started to have a little collection at my disposal. One instrument came into my possession when a fellow member of PRB "accidentally" bought it on eBay. As the saxhorn family are all designed to be just bigger or smaller versions of one another it's easy to not get a sense of scale when all you have is a photo of the instrument. That's one bonus of a group like PRB - if you get it wrong maybe someone else will have it.

The instruments above are:

- Couesnon & Cie (Paris, 1900) - This was the instrument bought "accidentally" by one of my colleagues. This has been a real addition to the group as Phil Dale also has a baritone saxhorn by Couesnon of the exact same date. All the "trimmings" are the same on the two instruments so they make a particularly fine pair.

- Boosey & Co. (London, c. 1900) - Richard Thomas used this on a couple of tracks on the PRB "Celebrated Distin Family" recording. We quite like altering the balance away from the more "modern" two sopranos/alto/tenor/bass (which is what the modern brass quintet provides) away to more in the middle i.e. soprano/two altos/tenor/bass, which is more typical of a lot of surviving brass chamber music of the time. This instrument is quite a heavy instrument because it has a type of compensating system - which makes the tuning more reliable.

- Rivet (Lyon, c. 1850), "Alto (*) Mib" - This is a really special instrument, it's quite light weight and it feels like a little tuba. There are interesting design elements - the tubing above the valves for instance that make it feel more in common with the bass instruments despite it's actual pitch.

- Courtois (Paris, c. 1855) "Alto" (*) saxhorn in F/E/E flat/D. Sold by Arthur Chappell (London) - on loan from the Jeremy Montagu Collection - This is an award winning horn - there are medals engraved in the bell from the exhibitions where it was displayed. The real bonus with this instrument is that Jeremy Montagu has almost all the crooks, two beautiful original mouthpieces and the original case (also in the picture). In the end I decided to use this instrument for the PRB "Celebrated Distin Family" recording - partially because I felt it blended well with the rest of the ensemble, partially because I found the set up of the instrument meant that the tuning was more flexible (I've grown to hate the middle C on most of these instruments), plus having the crooks were advantageous as I could make some decisions to put the instrument in different keys dependent on the piece of music we were playing.

(*) Just in case anyone is confused. All the saxhorns have two names. We have the French system, which would call these saxhorns, pitched in E flat, an "Alto", whilst in the UK we call the same thing a "Tenor". Just for simplicities sake, I tend to use the term tenor saxhorn.

ANNEKE SCOTT