Russian Revolutionaries Vol. I: Victor Ewald and Oskar Böhme

From St Petersburg: The musical soirées for brass instruments, established by the Emperor Alexander III when hereditary grand duke, are to take place again regularly every three weeks during the winter. The participants are the amateur grand dukes, the bandmasters of the regiments of the guard, and dilettanti of the first families of the nobility, altogether about 50 people. Boston Evening Transcript, 12 December 1881 (1).

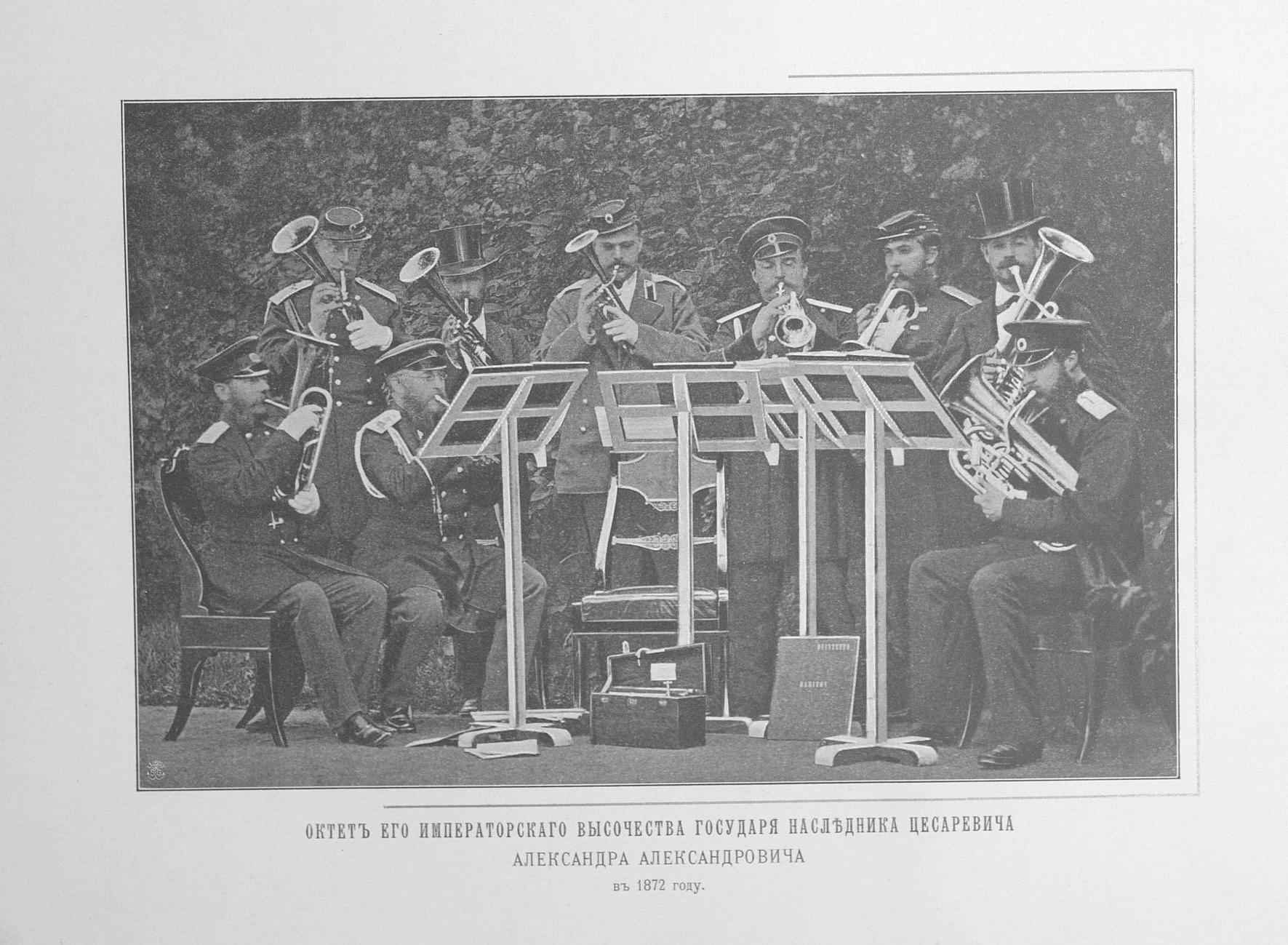

The Octet of the Imperial Highness Cesarevich Aleksandr Aleksandrovich, 1872.

Standing (l–r): Prince Alexander Petrovich Oldenburg, Franz Osipovich Berger, Grand Duke Alexander, Count Alexander Vasilyevich Olsufiev, Fyodor Andreyevich Schreder, Franz Osipovich Terner. Seated (l–r): General Mikhail Viktorovich Polovtsov, Count Adam Vasilyevich Olsufiev, Alexander Alexandrovich Bers.

К.В. Колокольцов Хор любителей духовой музыки, состоящий под августейшим государя императора покровительством 1858-1897 (Санкт-Петербург; скоропеч. “Надежда”, 1897).

The enjoyment of music, as listener or participant, has often been an element of aristocratic leisure time. For the Grand Duke Alexander of Russia (1845–94), an enthusiastic cornet player, it was his pleasure to meet every Thursday evening at 8pm at the Grand Hall of the Admiralty, with fellow aristocrats, other nobles and the bandmasters of the guard bands, to rehearse and perform brass chamber music.(2) The ‘Society of Wind Music Lovers’(3) was founded in 1872 and had grown out of an earlier smaller ensemble known as the ‘Octet of His Imperial Highness the Sovereign of the Tsarevich Alexander Alexandrovich’ founded by the Grand Duke (playing a cornet made by his favoured maker – Courtois), along with Count Adam Vasilyevich Olsufiev (cornet), Count Alexander Vasilyevich Olsufiev (cornet), Fyodor Andreyevich Schreder (cornet), Prince Alexander Petrovich Oldenburg (alto horn), General Mikhail Viktorovich Polovtsov (alto), Franz Osipovich Berger (alto), Franz Osipovich Terner (baritone) and Alexander Alexandrovich Bers (bass).(4) The Grand Duke continued to participate in his ensemble until his ascension to the throne in 1881 as Tsar Alexander III and was also known to play a tuba made by Courtois(5) and the helicon, an instrument that he was reported to have taken up when the pressures and responsibilities of being Tsar meant that regular cornet practice was no longer an option.(6)

The interest in brass instruments and participation in brass chamber music illustrates a view of brass instruments in Russia in the second half of the nineteenth century as ‘cutting edge technology’. This era had seen a drive towards improving standards and status in the music profession in Russia, with Anton Rubinstein (1829–94) and the Grand Duchess Yelena Pavlovna (1806–73) establishing the influential Russian Musical Society in 1859 which was followed by the pair founding the St Petersburg Conservatory in 1862. This new conservatoire was followed by both sister (Kiev and Kharkov in 1864, the Moscow Conservatory in 1866) and rival institutions (such as the anti- Germanic, pro-Russian institution, the Free Music School of St Petersburg in 1862). Earlier in the century Tsar Alexander II (1818–81) had sent Count Vladimir Alexandrovich Sollogub (1813–82) on a fact-finding mission to Paris and Brussels to study their conservatoires where he consulted musicians on how one would go about running such a venture, for example questioning the composer Giacomo Meyerbeer (1791–1864) on his views on potential candidates for director of a Russian conservatoire.(7) Eager to ensure the best from the start, Rubinstein ordered wind and brass instruments from the top makers in Vienna with which to furnish his new school.(8) This order for new instruments was linked to an ambitious plan, an Imperial Order, to impose a new pitch standard throughout the empire.(9) The desire to improve standards was not limited to the conservatoires. In 1873 Rimsky-Korsakov (1844–1908) blended his two careers in the navy and as a composer in his appointment as ‘Inspector of Naval Bands’,(10) a role designed to professionalise and improve the military ensembles. Throughout this period Russia looked to the rest of Europe for inspiration, though many, such as Balakirev (who believed that the new Conservatoire ‘threatened to turn Russian music into an outpost of Germany rather than a flourishing centre in its own right’)(11) feared it risked losing its own identity through slavish imitation of foreign styles ‘Russian’ chamber music for brass instruments abounds during the late-nineteenth century, though much of it was created by musicians who had travelled to Russia to forge their careers, such as the French composer

Antoine Simon (1850–1916) and the German composer Ludwig Wilhelm Maurer (1789– 1878). Alexander II, in his role as Grand Duke of Finland (Finland then being an autonomous part of the Russian Empire), oversaw a number of re-organisations of the Finnish Guards Band which morphed from a mixed wind and brass ensemble to a solely brass ensemble and included the particularly popular Finnish septet formation known as the torviseitskko, which consisted of cornet in E-flat, two cornets in B-flat, althorn in E-flat, tenorhorn in B-flat, euphonium and tuba — an instrumentation not dissimilar to that of the Böhme Trompeten Sextett es-Moll, Op. 30 included on this disc.

Artists from the rest of Europe began to visit Russia more frequently, with the two ‘schools’ of French and of German music vying for dominance. The visits in 1873 and subsequent years of Jean-Baptiste Arban (1825–89) and an ensemble of twelve soloists from the Chapelle in Paris(12) were an perfect exercise in the promotion of French music and musicians.(13) Arban was an ideal ambassador given that in 1859 he had been named as one of the ‘must-see attractions’ for discerning Russian tourists visiting Paris.(14) On one of these visits an elegant presentation copy of Arban’s Grande Méthode was given to the Grand Duke Alexander, presumably to complement the cornet lessons that Alexander had been having with Wilhelm (Vasily) Wurm (1826–1904), the German born ‘Cornet Soloist to His Imperial Majesty’ and director of Grand Duke Alexander’s band mentioned earlier. Many musicians, such as Wurm, travelled to Russia and stayed. The life of Oskar Böhme illustrates both the migration of such German musicians to Russia and the tragic impact of the Russian political situation on many of those who were innocently caught up in it.

Oskar Böhme was born on 24 February 1870 in Potschappel near Dresden and, like many musicians of this era, followed his father into a musical career. Böhme traveled and studied widely, initially in Hamburg (studying piano and theory with Cornelius Gurlitt, 1820–1901), Berlin (studying with Horowitz), both performing (in the Budapest Opera Orchestra) and studying (with Victor von Herzfeld, 1856– 1919)(15) in Budapest in 1894–96, which was followed by a year (1896–97) at the Leipzig Conservatory studying with Salomon Jadassohn (1831–1902).(16) Böhme finally emigrated to St Petersburg in 1897 where, by 1902, he was employed as a cornet player in the Imperial Mariinsky Theatre orchestra(17) remaining there until 1921 when he began teaching at the music school of the Leningrad Military College on Vasilevsky Island.(18) In 1930–34 he was a member of the orchestra of the Leningrad Drama Theatre.

In the period immediately after the October Revolution very little changed in terms of repertoire for musicians; however, the demographic of their audiences changed greatly, with free or cheap tickets being distributed. Workers, students, soldiers attended concerts, reacting with great respect and enthusiasm. The public appetite for music and participation in music making grew, though music was slower than other art forms to take the opportunity for new and experimental developments. The music scene changed drastically with the death of Vladimir Lenin (1870–1924) and the rise of Joseph Stalin (1878–1953), under whose rule music was subject to increasing control, with a growing range of music and musicians that were deemed unacceptable.

For Böhme things took a turn for the worse in the 1930s when he was swept up in Stalin’s ‘Great Terror’. These systematic purges inflicted between 1936 and 1938 identified many artists as dissenters or saboteurs and banished them to the inhospitable outskirts of the country. Böhme was first arrested in 1930 and then again on 13 April 1935. This second arrest led to his trial at a special meeting of the Narodnyĭ Komissariat Vnutrennikh Del (NKVD, the People’s Commissariat for Home Affairs) on 20 June of that year in which he was convicted of ‘participating in a counter-revolutionary organisation’. He was sentenced to three years exile in Orenburg (then known as Chkalov) where he continued to work, conducting the orchestra at the local cinema and teaching the local music school. Böhme was arrested for a third and final time on 15 June 1938. This time he was sentenced by a local NKVD troika to death on 30 October 1938 and shot soon afterwards.(19) This swift and brutal end is just one of many hundreds of thousands inflicted, often on spurious or non-existent evidence, under the notorious NKVD ‘Order No. 00447’ which had been issued on 30 July 1937. Order No. 00447 set out ‘a campaign of punitive measures against former kulaks, active anti-soviet elements, and criminals.’ It is thought that in the short period in which the Order was being acted upon, from August 1937 until mid-November 1938, in the region of 387,000 people were executed.

Böhme’s biography clearly indicates the importance that Böhme put on the study of composition, something which is reflected in his output. Like many performers of his era the focus is clearly on compositions for cornet or trumpet and includes a number of solo works for these instruments such as his Trumpet Concerto in E minor, Op. 18 and works for cornet/trumpet and piano such as the Berceuse, Op. 7, Entsagung, Op. 19, Serenade & Liebeslied, Op. 22, Soirée de St-Pétersbourg (Romanze), Op. 25, Ballet-Scene, Op. 31, and Russischer Tanz, Op. 32. These works exploit both the vocal lyricism of the instruments as well as a flamboyant virtuosity and would have been the mainstay of much of Böhme’s solo performances, given in extensive tours throughout Germany each year during his allocated four months of vacation from the Imperial Theatre orchestra.

The chamber works of Böhme cover a wide range of genres. Some, such as the Rokoko Suite, Op. 46 (published around or before 1928)(20) and the Fantasie über russische Volsklänge, Op. 45 (also published around or before 1928)(21) incorporate folksong, popular tunes and offer an early-twentieth-century interpretation of older forms such as the gavotte and minuet. Themes from the Fantasie über russische Volsklänge, Op. 45, may be recognisable to those familiar with Jules Levy’s (1838-1903) Grand Russian Fantasia which incorporates two of the same themes as the Böhme, opening with Aleksandr Varlamov’s (1801–1848) Krasnyǐ sarafan (‘The Red Dress’)(22) and also including the song Yekav Kozak za Dunaǐ (‘The Cossack riding to the Danube’)(23). Grand Duke Alexei Alexandrovich of Russia (1850–1908) had heard British born cornetist Levy performing in New York in 1871 and invited the virtuoso to visit Russia.(24) Later in life Levy detailed the inspiration behind this piece:

During a pause between Parts I and II of the programme a number of the ladies came to the piano besides which I stood and offered me their congratulations. They asked me whether I played Russian music, to which I was obliged to confess, that I was practically a stranger. They then asked me whether I would play a Russian song if they found the music for me, and I agreed to try. The sheet of music was produced, and I found that I should not only have to read it at sight, but transpose as well. The good humor and condescension of the ladies emboldened me, and I played it through without a mistake... The applause and honours were enthusiastic. I was told I played Russian music like a born Russian. Jules Levy, ‘At the court of the Czar’ in Philharmonic: A Magazine Devoted to Music, Art, Drama, 1902 (25)

In addition to the two themes appropriated by Levy, the Fantasie opens with a famous Thème russe known as Slava na nebe solntsu vyskomu (‘Glory to the Sun’)(26) which appears in Beethoven’s Second ‘Razumovsky’ Quartet as well as in Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov. The Fantasie also includes the songs Vozle rechki, vozle mostu (‘By the river, by the bridge’).(27) Given the small-scale ensemble and the simplicity of some of the Rokoko Suite in particular, these compositions may reflect Böhme’s pedagogical work.

The two Dreistimmige Fugen, Op. 28 (Präludium und Fuge, No. 1 in C minor, No. 2 in E-flat major), are much more thoughtful works, displaying Böhme’s thorough understanding of counterpoint. A choice of instrumentation has been given for these works; cornet or trumpet, althorn or horn and either tenorhorn, baritone or trombone. PRB have used these two pieces to explore the tonal contrasts between an ensemble of cornet, althorn and valve trombone (the dominant design of trombone in the nineteenth century)(29) and a more ‘symphonic’ ensemble of rotary valve trumpet, rotary valve horn and slide trombone. These two works, published in 1904, were not Böhme’s first explorations of these forms — as the Musikalisches Wochenblatt of 24 February 1898 reports a performance of a Praeludium, Fuge und Chorale by Böhme for two trumpets, horn and trombone, performed by a group of Leipzig Conservatory students on 8 February that year.(30)

Böhme’s Nachtmusik, Op. 44 offers two miniatures for brass quintet — not for the standard brass quintet instrumentation of the mid/late twentieth century (two trumpets, French horn, trombone, tuba), but instead for two cornets and three trombones. The ‘night- music’ is evoked in two nocturnal movements, a ‘Nokturno’ and a ‘Barkarole’, the traditional Venetian gondoliers’ song which was a popular form in Russia with many composers, including Tchaikovsky, Rimsky-Korakov, Balakirev, Rubinstein and Rachmaninov.

The Böhme Trompeten Sextett in E-flat major, Op. 30 was the work that inspired the PRB to begin researching and performing late- nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Russian chamber music for brass. It is not, despite its title, scored for a sextet of trumpets but for cornet, two trumpets (rotary instruments), bass trumpet or althorn, tenorhorn or trombone, and tuba. Whilst the sextet has remained in the repertoire it is more usually heard with bass trumpet/ althorn part performed on the French horn and the tenorhorn part on the trombone. The particular sonic world created by Böhme’s original instrumentation was something that PRB particularly wanted to explore.

* * * *

If Oskar Böhme can be seen as a professional musician émigré to Russia then Victor Ewald can be seen to represent the choices native Russian citizens had in terms of musical careers. Victor Ewald was born in St Petersburg on 27 November 1860. In late-nineteenth-century Russia the status of musicians was very precarious. Other artistic professions, such as painters, sculptors and actors were deemed svobodnyǐ khudozhnik (‘free artists’),(31) which exempted them from various taxes and military service, and enabled them to settle anywhere in the country. Musicians were less fortunate and, in effect, held the same status as a peasant. This may go some way to explain the number of leading composers and musicians during this period who pursued another professions in addition to their musical careers such as César Cui (a military engineer, 1835–1918), Modest Mussorgsky (a civil servant, 1839–81), Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (officer in the Imperial Russian Navy, 1844–1908), Alexander Borodin (a chemist, 1833–87), Mily Balakirev (1837–1910, who worked for a time in the goods department of the Warsaw railway) and Victor Ewald (a civil engineer, 1860–1935).

In the same way as the Grand Duke Alexander participated in regular brass ensemble evenings, Victor Ewald found himself participating in the chamber music evenings organised by Mitrofan Petrovich Belyayev (1836–1904). Belyayev was the head of a highly successful timber business and an active supporter of Russian music, having established a concert series dedicated to Russian music and having founded his publishing house (Edition M.P. Belaïeff, Leipzig) which was dedicated to the publication of Russian music. The publications of M.P. Belaïeff included that Ewald’s Quintet in B-flat minor, Op. 5.(32) Belyayev also organised his regular Friday evening string quartets at his house in St Petersburg, performing on the viola and joined by Professor Nikolai Aleksandrovich Gesekhus (1845-1919) and Dr. Aleksandr F. Gelbke (b.1848) on violin and Ewald on cello.(33) Ewald was not the initial cellist for this ensemble, his predecessor being Mikhail Nikolsky (1848–1917) who was embroiled in the fallout of the assassination attempt on Alexander II and forced to flee to Kiev, later being exiled to Siberia.(34) This ensemble performed both the classics of composers such as Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven and new compositions by friends and members of their circle including Borodin, Glazunov, and Rimsky-Korsakov, as well as works by the quartet’s members themselves.

Ewald’s musical training took place from the age of twelve at the St Petersburg School of music where, according to André Smith, the young Ewald had lessons on the cornet from Wilhelm Wurm (the teacher mentioned earlier of the Grand Duke, later Tsar Alexander III)(35) in addition to studying piano, horn, cello, harmony and composition. This musical education went alongside his studies at the St Petersburg School of Construction (later known as the Institute for Civil Engineers, and later still the Leningrad Communal Building and Engineers Institute) from which Ewald graduated in 1883. Ewald went on to complete his doctorate at this institution and then joined the faculty rising to the position of ‘Honoured Professor’.(36)

In the musical sphere Ewald’s earliest publications were via Belyayev’s publishing house and included the String Quartet in C major, Op. 1 (1894), a Romance for cello and piano, Op. 2 (1894), Deux Morceaux for cello and piano, Op. 3 (1894) and a Quintet for two violins, two violas and cello, Op. 4 (1895). The String Quartet in C major, Op. 1 is thought to have originally been a brass quintet.(37) Ewald admitted to his son-in-law Yevgeny Gippius (1903–85) that he had been inspired by visiting virtuoso brass players of the time such as Julius Kosleck (1825–1905), a cornet player and promoter of Václav Frantisek Červeny's (1819–96) Kaiser-Cornets. Ewald believed this had led to him being too adventurous in his writing in this composition. Rather than abandon the work, Ewald chose to recycle it later as a string quartet, entering the latter version into the St Petersburg Quartet Society competition of March 1893. This competition was judged by Tchaikovsky (1840–93), Rimsky-Korsakov and Herman Laroche (1845–1904) who awarded Ewald joint third place.(38)

Despite this apparent early Ewald quintet it is the Quintet in B-flat minor, Op. 5 (published by M.P. Belaïev in 1912), which is colloquially known as the ‘first’ of Ewald’s quintets and which was thought for many years to be the only brass quintet by Ewald. As it is the only one of the four quintets to have been published during his lifetime it is the only one of these works that we can offer up a date (of publication rather than composition) that is not highly speculative.

The story of the ‘second’ Quintet in E-flat major, Op. 6, is a little more uncertain. Much of the information on Ewald that we have today is thanks to the musicologist, and former bass trombonist of the Metropolitan Opera House in New York, André Smith. In the late 1950s/1960s Smith’s interest in Russian music was encouraged by Gustave Reese (1899–1977) to whom Smith was a teaching assistant at the Julliard School of Music in New York. Given the difficulties of obtaining information from Russia directly at this time, Reese encouraged Smith to make contact with Boris Schwartz (1906–83).(39) One of Schwartz’s correspondents in Russia was composer and Soviet musicologist Viktor Mikhaylovich Belyayev (1888–1968) who had studied with friends of Ewald’s(40) and who knew of the existence of brass quintets (plural) by Ewald. Smith recounts(41) that Belyayev took the initiative and contacted Ewald’s son-in-law, Yevgeny Gippius who decided to give the manuscripts of three additional works to Smith. Smith held off publishing or otherwise disseminating these three quintets, initially citing the importance of first verifying the authenticity of the newly discovered works.(42) Unfortunately, to date, Smith has not published his sources and his publication on Ewald, announced in 1994, has yet to appear.(43)

In 1972 the American Brass Quintet (ABQ) approached Smith with a view to including the additional Ewald Quintets in their 1974–75 season as the quintet was keen to focus on nineteenth-century repertoire in their programming. The first event in this celebration was a performance of the Quintet in E-flat Major, Op. 6, as part of an ABQ concert at the Carnegie Recital Hall on the 18th of November, 1974. Following performances of all four quintets Smith was contacted by the principal horn of the Leningrad Philharmonic, Vitaly Buyanovsky (1928–93), who was eager to see the quintets. Smith sent his parts to the second (Op. 6) and third (Op. 7) quintets, retaining the fourth quintet (Op. 8) as he was ‘not yet satisfied with their accuracy’(44) and because the ABQ had exclusivity on this quintet for a year. Apparently Buyanovsky misinterpreted Smith’s insistence that the parts not be shared further and made his own copies of the two quintets which he then shared freely.

One of Buyanovsky’s pupils was the eminent Norwegian horn player Frøydis Ree Wekre (b. 1941). Ree Wekre made numerous copies of music she encountered during her studies. This included the Ewald Op. 6 and Op. 7 quintets which she later shared with the Empire Brass Quintet.(45) Many contemporary editions of the second and third quintets appear to be offshoots of the Ree Wekre sources and make the fundamental change of altering the instrumentation from two cornets, althorn, tenorhorn and tuba to the more standard modern brass quintet of two trumpets, French horn, trombone and tuba. This raises the question of what other alterations have occurred. It would be erroneous to suggest that Ree Wekre’s sources were necessarily of Buyanovsky’s edition from Smith (thus providing an intriguing thread of Ewald–Gippius–Smith– Buyanovsky–Ree Wekre–Empire Brass)(46) given that Ree Wekre’s studies in the autumn of 1967, the spring of 1968, and visits in subsequent years(47) appear to be prior to Smith sharing his version with Buyanovsky (post 1974 at the earliest), thus suggesting another source. Indeed a set of parts to the Quintet in E-flat major, Op. 6 exist in the music library of the St Petersburg Philharmonic and it is these, with the kind permission of the library, that PRB have used. The parts are hand written on manuscript paper from the hugely productive printing firm of Ivan Dmitrievich Sytin (1851–1934) based in Valovaya ulitsa (‘Gross Street’) Moscow. This publishing house (‘The Association of Printing, Publishing and Book Trade ID Sytin and Co.’)(48) was subsumed by the State Publishing House in 1919 and this set of parts was consigned to the Philharmonic library in 1950.

* * * *

The twin influences of Germany and France can be seen in the instruments popular in late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century Russia. In 1862, Anton Rubinstein turned to Viennese makers to supply brass instruments for the fledgling St Petersburg Conservatory.(49) The instruments of Julius Heinrich Zimmermann (1851–1922) were favoured by players including cornet player Willy Brandt (a.k.a. Vasily Georgievich Brandt, 1869–1923)(50) and trumpet player Mikhail Innokentevich Tabakov (1877–1956)(51) though some, such as Adolf Fredrik Leander (1833–99) director of the Helsinki Guards Band, criticised them due to their weight, preferring instead instruments by the German maker Kruspe (Erfurt) or the Parisian maker Courtois.(52) Willy Brandt’s preference for German instruments extended to his choice of trumpet — a B-flat rotary valve instrument by Heckel.(53) German born Zimmermann set up his business in St Petersburg in 1876 supplying military instruments to the Russian army.(54) The firm grew rapidly, supplying instruments and sheet music and with branches in Leipzig, Moscow, London, Riga and Berlin. A preference for Austro/Germanic makers could be seen in the appointment of Franz Eschenbach as maker to Tsar Alexander III in around 1882.(55) Business for Franz must have been thriving as Carl August Eschenbach (1821–98), the Royal Saxon Court instrument maker and father of Franz, sold up his Dresden business in 1897 in order to move to St Petersburg and join his son.(56)

The French style of instrument, and in particular the instruments chosen by ‘cornet-à-piston’ players, reflect the influence of Arban and other French performers. Courtois, mentioned above, was a favoured maker of many including Tsar Alexander III, Oskar Böhme, Jean-Baptiste Arban, Wilhelm Wurm (Courtois made a Modele W. Wurm mouthpiece) and Jules Levy.(57) In 1888 the Belgian maker Mahillon was commissioned to provide all the brass instruments for the newly formed St Petersburg Philharmonic.

This mixture of French and German makers is reflected in PRB’s choice of instruments for this ‘Russian Revolutionaries’ disc. French cornet-à-pistons by Couesnon and Besson were chosen alongside German-made trumpets, horns, trombones and tubas. Russian performance practice embraced both the rotary and piston valve to an equal extent as can be seen by the inclusion of illustrations of both designs of instruments in trombonist Vladislav Mikhailovich Blazhevich’s (1881– 1942) 1939 series of instruction manuals for all wind and brass.(58) As is common with other geographical areas of this period, the nomenclature of some of the inner parts can initially be confusing as the term ‘althorn’ indicated the German/Eastern European instrument in E-flat (i.e. the same pitch as the British tenor horn), an instrument similar to a mirror-imaged Wagner Tuba i.e. with the valves operated by the right hand. Frequently Waldhorn, a generic term for the French horn, is given as an alternative for the althorn with the specification that it is pitched in E-flat. Similarly the term tenorhorn indicates the same instrument but at the lower pitch of B-flat (i.e. the same pitch as the British baritone), and is often used interchangeably with the term baritone, an instrument of the same pitch but with a larger bore, bell profile and, in some designs, a fourth valve. The trombone is also given as an alternative instrument.

It is especially important to note the sonic differences between the symphonic brass instruments (trumpets, horns, trombones) of the time and the instruments more traditionally associated with bands (cornets, althorns and baritones). Today the Ewald Quintets in particular are very well known as a mainstay of the ‘modern’ brass quintet repertoire and are frequently heard performed on two trumpets, horn, trombone and tuba instead of the original instrumentation of two cornets, althorn, baritone and tuba. The combination of these five conical-bored instruments provides a much more mellow and homogeneous timbre than the modern incarnation. Many of the Böhme works on this disc give alternatives, cornet or trumpet, althorn or horn, baritone or trombone; PRB have often chosen to favour the conical band instruments over the symphonic counterparts in part due to the scarcity of interpretations on these rarer instruments. The contrast between the two options can be most clearly heard in Böhme’s Dreistimmige Fugen Op. 28, the first using cornet/althorn/valve trombone and the second trumpet/horn/slide trombone.

© 2017 Anneke Scott

Footnotes:

(1) The Tsar was well known for his love of brass playing: “The Emperor in his leisure moments tries to do the same for his boys. Especially he loves to give them music and dancing lessons, for he thinks himself a great musician, and has a predilection for the cornet-à-piston. One day a minister, busy reading to him an important document, beheld the Czar vanish suddenly to intone in the adjoining room a rhapsody on his favourite instrument .”Excuse me,” he said, returning after half and hour, “but I had so lovely an inspiration.” “Politikos’ (pseud) “The Emperor of Russia” The sovereigns and courts of Europe (London: T. F. Unwin, 1891), 47.

(2) Общество любителей духовой музыки, see К.В. Колокольцов Хор любителей духовой музыки, состоящий под августейшим государя императора покровительством 1858-1897 (Санкт-Петербург; скоропеч. “Надежда”, 1897). K.V. Kolokoltsov Khor Lyubitelej dukhovoj muzyki, sostoyashchij pod avgustejshim gosudarya imperatora pokrovitelstvom 1858–1897 (Sankt-Peterburg; skoropech. “Nadezhda”, 1897). [Konstantin Vasilievich Kolokoltsov The choir of the Wind Music Lovers Club under the auspices of the Emperor: 1858-1897 (St. Petersburg Skoropech. "Hope", 1897)], 23.

(3) Общество любителей духовой музыки, see К.В. Колокольцов Хор любителей духовой музыки, состоящий под августейшим государя императора покровительством 1858-1897 (Санкт-Петербург; скоропеч. “Надежда”, 1897). K.V. Kolokoltsov Khor Lyubitelej dukhovoj muzyki, sostoyashchij pod avgustejshim gosudarya imperatora pokrovitelstvom 1858–1897 (Sankt-Peterburg; skoropech. “Nadezhda”, 1897). [K.V. Kolokoltsov The choir of the Wind Music Lovers Club under the auspices of the Emperor: 1858-1897 (St. Petersburg Skoropech. "Hope", 1897)].

(4) Общество любителей духовой музыки, see К.В. Колокольцов Хор любителей духовой музыки, состоящий под августейшим государя императора покровительством 1858-1897 (Санкт-Петербург; скоропеч. “Надежда”, 1897). K.V. Kolokoltsov Khor Lyubitelej dukhovoj muzyki, sostoyashchij pod avgustejshim gosudarya imperatora pokrovitelstvom 1858–1897 (Sankt-Peterburg; skoropech. “Nadezhda”, 1897). [K.V. Kolokoltsov The choir of the Wind Music Lovers Club under the auspices of the Emperor: 1858-1897 (St. Petersburg Skoropech. "Hope", 1897)]

(5) Общество любителей духовой музыки, see К.В. Колокольцов Хор любителей духовой музыки, состоящий под августейшим государя императора покровительством 1858-1897 (Санкт-Петербург; скоропеч. “Надежда”, 1897). K.V. Kolokoltsov Khor Lyubitelej dukhovoj muzyki, sostoyashchij pod avgustejshim gosudarya imperatora pokrovitelstvom 1858–1897 (Sankt-Peterburg; skoropech. “Nadezhda”, 1897). [K.V. Kolokoltsov The choir of the Wind Music Lovers Club under the auspices of the Emperor: 1858-1897 (St. Petersburg Skoropech. "Hope", 1897)], 21.

(6) “Musical evenings at which celebrated artists take part, are very rare at the court of the Czar now. The late Emperor was passionately fond of music, and was in his youth an excellent performer on the cornet-a-piston. Prof. Wurm had been teaching him for ten years, and even to-day praises the zeal and the talent of his illustrious pupil. When later on he became so much occupied with the government business, he had to give up his favourite instrument, as he had no time to practice. “But we won’t give up music quite,” he remarked to Prof. Wurm. “Now I shall choose the great saxtuba.” He founded his own brass band of about forty performers, mostly officers and begged the conductor to treat them all sans façon, for certainly otherwise nothing sensible would come of it. At the head of them sat the Czar, his gigantic instrument slung around him, and tooted bravely with the rest.” Werner's magazine. v.23.(March-August, 1899), 575.

(7) Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 49/12 (17th of September 1858); 129. Also Sabine Henze-Döhring Giacomo Meyerbeer, Briefwechsel und Tagebücher, vol 7, (Berlin/New York: Walter de Gruyter, 2004), 339-40.

(8) “A Rubinstein hat, wie die Zellner'schen "Blätter für Musik" berichten, während seines neulichen Aufenthaltes in Wien bei den dortigen Blasinstrumentenfabrikaten Instrumente für ein vollständiges Orchester nach der neuen Stimmung, die zufolge kaiserlichen Befehls im ganzen Reiche einzuführen ist, bestellt. Uebrigens sind die in Wien bestellten Instrumente für das Petersburger Conservatoirum bestimmt, welches am 1. September unter Rubinstein's Leitung eröffnet wird.” Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 57/8 (August 22, 1862), 72.

(9) Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 57/8 (22nd of August, 1862); 72.

(10) Nikolay Andreyevich Rimsky-Korsakov, My Musical Life trans. J. Joffe (New York, 1936), 116 f.

(11) David Fanning, “Russia: East Meets West” in ed. Jim Samson, The Late Romantic Era: From the mid-19th century to World War I (London: Macmillan, 1991), 182.

(12) “Der Pariser Orchesterdirigent Arban ist nach Petersburg abgereift um die Leitung der in Pawlowski stattfindenden Vauxhall-Concerte zu übernehmen. Er hat zwolf de besten Solisten aus seiner Pariser Capelle mitegnommen.” (“Arban, the Parisian orchestral conductor, has departed to Petersburg to take over the direction of the Vauxhall concerts, held in Pavlovsk. He has taken twelve of the best soloists from his Capelle Capelle.” Signale für die musikalische Welt, vol. 34, no. 35 (Leipzig: May 1876), 554

(13) Letter from Jean-Baptiste Arban to Ambroise Thomas (director of the Conservatoire) 23rd of April, 1873: “Jusqu’à présent les Alledmands ont eu exclusivement le privilège de faire entendre de la musique dans cette capital oú la musique française est très estimée, mais presque complètement délaissée, eu égard au monopole. Saissant l'occasion qui m'est offerte, j'ai à cœur de faire entendre dans mes concerts, tous les chefs-d'œuvre de l'Ecole Française et pour assurer mon succès, je suis autorisé par la Direction de Russie, d'engager douze des Meilleurs solistes de Paris” [“Until now, the Germans have had the exclusive privilege of making music heard in this capital [St. Petersburg], where French music is highly esteemed, but almost completely abandoned, in view of the monopoly. I have the opportunity to hear all the masterpieces of the French School and to ensure my success, I am authorised by the Directorate of Russia to hire twelve of the best soloists of Paris”], quoted in Jean-Pierre Mathiez Joseph Jean-Baptiste Laurent Arban (1823–1889) (Moudon: Editions Bim, 1977), 25.

The French newspapers reported this first tour with enthusiasm: “Arban partira le 8 mai pour Saint-Pétersbourg, où il est engagé, ainsi que les principaux solistes de son orchestre. Il donnera des concerts d’été dans un établissement magnifique nouvellement institué. Le public russe accueillera M. Arban, nous en sommes convaineu à l’avance, avec toute la sympathie que mérite son double talent de chef d’orchestre et de compositeur.” [“Arban will leave for St. Petersburg on 8 May, where he is engaged, as well as the principal soloists of his orchestra. He will give summer concerts in a beautifully newly established establishment. The Russian public will welcome Mr. Arban, and we are convinced of it in advance, with all the sympathy which his dual talents as conductor and composer deserve.”] Le Ménestrel May, 4 1873, 184.

Future excursions were not permitted by the Conservatoire which necessitated Arban’s resignation: “Arban, n’ayant pu obtenir au Conservatoire le congé qu’il avait sollicité pour se rendre à Saint-Petersbourg, a donné sa démission. M. Maury son suppléant habituel, le remplace comme professeur de cornet à pistons.” [“Arban, having been unable to obtain At the Conservatoire, the leave he had requested to go to St. Petersburg, resigned. M. Maury, his usual substitute, replaces him as a cornet-teacher.”] “Faits Divers” Le Chronique Musicale, vol. 4 May 15, 1874, 188. This news was reported widely: “M. Arban, the celebrated performer on the cornet-a-piston, has also resigned his professorship in the same Conservatoire, in consequence of his being refused leave of absence for a journey to St. Petersburg. M. Maury is named as likely to succeed him.” The Academy and Literature vol. 5, June 6, 1874, 650.

(14) “Curiosités Parisiennes: Le Casion” in La Russie à Paris. Guide du Voyageur Russe (Paris: Librairie Nouvelle/St Petersburg: Issakoff/Dufour/Moscow: Gauthier, 1859) 103: “que les concerts des mardis, jeudis et samedis, conduits pàr Arban, notre célèbre piston, sont très-suivis et applaudis par les amateurs de bonne musique.”

(15) See Oskar Böhme’s entrance certificate from the Leipzig Conservatory (November 2, 1896). Reproduced (fig. 5-2) and quoted in Edward Tarr East Meets West: The Russian Trumpet Tradition from the Time of Peter the Great to the October Revolution (New York: Pendragon Press, 2003), 204–205.

(16) See above plus Oskar Böhme's Teachers’ Report from the Leipzig Conservatory (December, 3 1897). Again reproduced (fig. 5-3) and quoted in Edward Tarr East Meets West: The Russian Trumpet Tradition from the Time of Peter the Great to the October Revolution (New York: Pendragon Press, 2003), 205–206.

(17) Ezegodnik imperatorskikh teatrov [Yearbook of the Imperial Theaters] (St. Petersburg: Printing Office of the Imperial Theatres, 1902–1903), 81.

(18) Bruce Briney, The Development of Russian Trumpet Methodology and Its Influence on the American School, (DMA diss., Northwestern University, 1997), 42.

(19) Anatoly Yakovlevich Rasumov Ленинградский мартиролог/Leningradskiy Martirolog [The Leningrad Martyrology] vol. 12, (Санкт-Петербург: «Возвращённые имена» при Российской Национальной библиотеке, 2012/Sankt-Peterburg: “Vozvrashchyonnye imena” pri Rossiĭskoĭ Natsional’noĭ biblioteke, 2012), [(St. Petersburg: “Returned Names”, Russian National Library, 2012)]. “Boehme Oscar Wilhelmowicz, born in 1870, native of Dresden, German, non-partisan, musician of the Opera and Ballet Theater and teacher of the Musical College, lived: Leningrad, VO, 3rd line, 26, sq. . 1. Arrested in 1930. He was arrested again on April 13, 1935. On June 20, 1935, at a special meeting of the NKVD of the USSR, he was convicted of "participation in a counter-revolutionary organization" for 3 years of exile. He served time in Orenburg, conductor of the orchestra at the Oktyabr cinema. Arrested on June 15, 1938 by the Troika of the NKVD of the Orenburg Region. October 30, 1938. sentenced under art. Art. 58-1a-11 of the Criminal Code of the RSFSR to the death penalty. He was shot in Orenburg on October 3, 1938 (Bame in the Book of Remembrance of Victims of Political Repression in the Orenburg Region.).” “Беме Оскар Вильгельмович, 1870 г. р., уроженец г. Дрезден, немец, беспартийный, музыкант Театра оперы и балета и преподаватель Музыкального техникума, проживал: г. Ленинград, В. О., 3-я линия, д. 26, кв. 1. Арестовывался в 1930 г. Вторично арестован 13 апреля 1935 г. Особым совещанием при НКВД СССР 20 июня 1935 г. осужден за «участие в контрреволюционной организации» на 3 года ссылки. Отбывал срок в г. Оренбург, дирижер оркестра в кинотеатре «Октябрь». Арестован 15 июня 1938 г. Тройкой УНКВД Оренбургской обл. 30 октября 1938 г. приговорен по ст. ст. 58-1а-11 УК РСФСР к высшей мере наказания. Расстрелян в г. Оренбург 3 октября 1938 г. (Бэме в Книге памяти жертв политических репрессий в Оренбургской области.).”

(20) Date based on the Rühle & Wendling, Leipzig edition of this work which gives a copyright of 1928. Plate number R.u.W.3129 may lead to future further clarification of the publication date.

(21) Date based on the Rühle & Wendling, Leipzig edition of this work which gives a copyright of 1928. Plate number R.u.W.3130 may lead to future further clarification of the publication date.

(22) Aleksandr Varlamov, Красный Сарафан, Krasnyǐ sarafan, [The Red Dress].

(23) Traditional, ехав козак за дунай, Yekav Kozak za Dunaǐ, [The Cossack riding to the Danube]. Nikolai Lvov Собрание Нородных Рускых Песен с их Голосами на Музыку положил Иван Прач/Sobraniye Norodnykh Ruskykh Pesen s ikh Golosami na Muzyku polozhil Ivan Prach, [Collection Οf Native Russian Songs With their Parts Put into music by Ivan Prach, ed. V.M.Belyaev (государственноие музыкальное издателство; Москва, 1955/Gosudarstvennoe muzykalnoe izdatelstvo; Moskva, 1955 [State Musical Publishing House; Moscow, 1955]), 309–10.

(24) Jules Levy’s “At the court of the Czar” in Philharmonic: A Magazine Devoted to Music, Art, Drama, vol. 2 (1902), 144.

(25) Jules Levy, “At the court of the Czar” in Philharmonic: A Magazine Devoted to Music, Art, Drama, vol. 2 (1902), 144–149.

(26) Traditional, слава на небе солнцу выскому, Slava na nebe solntzu vyskomu, [Glory to the Sun]. Nikolai Lvov Собрание Нородных Рускых Песен с их Голосами на Музыку положил Иван Прач (Типографии Горкачо училища, 1790)/Sobraniye Norodnykh Ruskykh Pesen s ikh Golosami na Muzyku polozhil Ivan Prach, (Tipografii Gorkacho uchilishcha, 1790) [Collection Οf Native Russian Songs With their Parts Put into music by Ivan Prach, (The Printing houses, Gorkacho School, 1790)]. Reprint by State Musical Publishing House, Moscow, 1955, 283–84.

(27) Traditional, возле речки, возле мосту, Vozle rechki, vozle mostu ,[By the river, by the bridge]. Nikolai Lvov Собрание Нородных Рускых Песен с их Голосами на Музыку положил Иван Прач (Типографии Горкачо училища, 1790)/Sobraniye Norodnykh Ruskykh Pesen s ikh Golosami na Muzyku polozhil Ivan Prach, (Tipografii Gorkacho uchilishcha, 1790) [Collection Οf Native Russian Songs With their Parts Put into music by Ivan Prach, (The Printing houses, Gorkacho School, 1790)]. Reprint by State Musical Publishing House, Moscow, 1955, 217–18.

(28) Trevor Herbert, “Valve trombones and other ninteenth-century introductions,” in The Trombone (New Haven/London: Yale University Press, 2006), 182–203.

(29) Dates verified using the P.Jurgenson Leipzig/Moscow plate numbers 29809 and 29810.

(30) Musikalisches Wochenblatt vol. 9, no. 29 (February 24, 1898), 133. Musicians included trumpeters Naumann and Steuber (both from Leipzig, horn player Helm (from Wilsdruff) and trombonist Handke.

(31) Richard Taruskin, Defining Russia Musically: Historical and Hermeneutical Essays, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001),xii

(32) See Friedrich HofmeisterVerzeichnis der in Deutschland seit 1860 erschienenen Wekre Russischer Komponisten (Leipzig: Friedrich Hofmeister Verlag, 1950).

(33) M. Montague-Nathan, “Belaiev, Maecenas of Russian Music,” Musical Quarterly, IV (July, 1918), 464 (NB “Hesekhus”). Also Nicolay Rimsky-Korsakov My Musical Life, trans. Judah A. Joffe, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1925), 227. Full names and birth/death dates of Gesekhus and Gelbke from Mary S. Woodside The Russian Life of R.-Aloys Mooser, Music Critic to the Tsars: Memoirs and Selected Writings (Lewiston, New York; Edwin Mellen Press, 2008),137.

(34) André Smith “Victor Vladimirovich Ewald (1860–1935): Civil Engineer & Musician” International Trumpet Guild Journal vol. 18, no. 3 (February, 1994), 11.

(35) André Smith “Victor Vladimirovich Ewald (1860–1935): Civil Engineer & Musician” vol. 18, no. 3 International Trumpet Guild Journal, (February, 1994), 7.

(36) This information comes from the “In Memorium Professor V. V. Ewald (1860–1935) quoted in André Smith “Victor Vladimirovich Ewald (1860–1935): Civil Engineer & Musician” vol. 18, no. 3, International Trumpet Guild Journal, (February, 1994), 14. Original comes from Stroitelnie materiali [The Building Materials] 4:58, 1935.

(37) André Smith “The history of the four quintets by Victor Ewald” International Trumpet Guild Journal vol. 18, no. 4, (May, 1994), 6 states that the composition was inspired by Ewald’s encounters with the Berlin cornet player Julius Kosleck (1825–1905) and Oskar Böhme.

(38) Nicolay Rimsky-Korsakov My Musical Life, trans. Judah A. Joffe, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1925), 283.

(39) Professor of music at Queens College in New York, and Russian born.

(40) Anatoli Liadov (1854–1914), Jāzeps Vītols a.k.a. Joseph Wihtol (1863–1948) and Aleksandr Konstantinovich Glazunov (1865–1936).

(41) André Smith “The history of the four quintets by Victor Ewald” International Trumpet Guild Journal vol. 18, no. 4 (May, 1994), 4-33.

(42) Through continued correspondence with Schwartz and Gippius as well as gathering the recollections of Alfred Julius Swan (1890–1970), Vincent Bach (1890–1976), Adriana Mikéshina (1896–1979), Arkady Kouguell (1898–1985) and Victor Manusevitch (1902–83) see André Smith “The history of the four quintets by Victor Ewald” International Trumpet Guild Journal vol. 18, no. 4 (May, 1994), 19, fn.31.

(43) André Smith “The History of the Four Quintets for Brass by Victor Ewald,” in International Trumpet Guild Journal vol. 18, no. 4 (May, 1994), 26.

(44) André Smith “The history of the four quintets by Victor Ewald” International Trumpet Guild Journal vol. 18, no. 4 (May, 1994), 21.

(45) In 1976 according to David F. Rees Victor Ewald and the Russian Chamber Brass School (PhD dissertation, Eastman School of Music, 1979). In private correspondence between Frøydis Ree Wekre and Anneke Scott (email, June 5, 2016). Ree Wekre dates the encounter “in the early or mid seventies”.

(46) André Smith “The History of the Four Quintets for Brass by Victor Ewald,” in International Trumpet Guild Journal vol. 18, no. 4 (May, 1994), 26.

(47) Source - private correspondence between Frøydis Ree Wekre and Anneke Scott (email, June 5, 2016). Unfortunately Ree Wekre no longer has copies of her sources.

(48) Товарищество печатания, издательства и книжной торговли И.Д. Сытина и К°/ Tovarishchestvo pechataniya, izdatel’stva i knizhnoĭ togrovli I.D.Sytina i Ko.

(49) “A Rubinstein hat, wie die Zellner'schen "Blätter für Musik" berichten, während seines neulichen Aufenthaltes in Wien bei den dortigen Blasinstrumentenfabrikaten Instrumente für ein vollständiges Orchester nach der neuen Stimmung, die zufolge kaiserlichen Befehls im ganzen Reiche einzuführen ist, bestellt. Uebrigens sind die in Wien bestellten Instrumente für das Petersburger Conservatoirum bestimmt, welches am 1. September unter Rubinstein's Leitung eröffnet wird.” Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 57/8 (August 22, 1862), 72.

(50) Edward Tarr East Meets West: The Russian Trumpet Tradition from the Time of Peter the Great to the October Revolution (New York: Pendragon Press, 2003), 188 fig. 4-7 and 189, fn. 73.

(51) Edward Tarr East Meets West: The Russian Trumpet Tradition from the Time of Peter the Great to the October Revolution (New York: Pendragon Press, 2003), 369. NB. Tabakov’s Zimmermann B-flat trumpet is part of the M.I.Glinka Museum of Musical Culture (Moscow) collection.

(52) Kauko Karjalainen, "The Brass Band Tradition in Finland" vol. 9 Historic Brass Society Journal (1997), 86.

(53) Edward Tarr East Meets West: The Russian Trumpet Tradition from the Time of Peter the Great to the October Revolution (New York: Pendragon Press, 2003), 400.

(54) Günther Jopping, preface to the reprint of Musikinstrumente-Katalog (Musikverlag Zimmermann: Frankfurt, 1984. Original: J.H.Zimmermann: Leipzig, c. 1899).

(55) William Waterhouse The New Langwill Index: A Dictionary of Musical Wind-Instrument Makers and Inventors, (London: Tony Bingham, 1993), 108.

(56) William Waterhouse The New Langwill Index: A Dictionary of Musical Wind-Instrument Makers and Inventors, (London: Tony Bingham, 1993), 108.

(57) See names listed in Antoine Courtois advert in Émile Coyon and Bettinger Annuaire musical et orphéonique de France, vol. I (Paris: Aureau, 1875), 309.

(58) André Smith “The history of the four quintets by Victor Ewald,” International Trumpet Guild Journal vol. 18, no. 4, (May, 1994), 13, fig. 20 taken from Vladislav Mikhailovich Blazhevich Shokola kollektivnoi igry na dukhovykh instrumentakh primenitel’no k tseliam nachal’nogo obucheniia igre na otdel’nykh instrumentakh dukhovogo orkestra (Gosudarstvennoe Muzykal’noe Izdatel’stvo, Moscow, 1935). [Vladislav Mikhailovich Blazhevich School of Ensemble Playing for Wind Instruments Adapted for the Use of Beginning Students and the Instruction of Wind Ensemble (State Music Publishing House, Moscow, 1935)].